Some months ago I played League of Legends for the first time with a group of friends. The plan was to do a LAN party together. We met one evening and one by one we booted up the launcher in rows, queuing gleefully into the gathering storm cloud of our very first match. The group’s experience levels were far-ranging: myself and a few others represented the measly newcomers, humble squires in a game of knights; and at the other end towered the forms of friends who had been playing for years. I was systematically destroyed. It was fun to do something with friends, people I care about, but the game itself I found somewhat frustrating, not especially enjoyable. I rode home happy to have tried it, but knowing I would probably never play again. But as the week went on, I found myself still thinking about it. What was odd to me wasn’t that I was interested in a game I thought I had disliked – sometimes a work grows on me over time. No, what was strange is that I wasn’t thinking at all of the game’s actual elements – what sorts of strategic alternatives I might have tried, new modes of play – but rather the obliviatory flow state itself. It was like a hunger swelling inside me. It felt an awful lot like addiction.

And since then I’ve been thinking a lot about addiction in games. I’ve started to notice it everywhere – not just in loot boxes and gacha games, but in linear narrative games, and, perhaps most troubling, in independent “hobbyist” games (a term I use here to mean works removed from the marketplace). It feels like I can’t stop seeing it, and I have found myself suddenly awake to how deep this force lives within the cracks of the art form. The questions I’ve been wondering about are: how deep has it gotten? in what ways has it corrupted play, if at all? and is there any escaping this?

In Natasha Schüll’s fantastically rigorous examination of casino games, Addiction by Design, she investigates the nature of gambling games and the dark power they hold over us. One of the first things she dispels is the idea that gamblers are playing for money – early in the book she writes that they’re not playing to win, but rather “to keep playing – to stay in that machine zone where nothing else matters.” One player explains that if she does win at a slot machine, whatever rush she may feel derives not from monetary payouts, but from the ability to keep playing. It is all in service of “the machine zone,” which one person describes “like being in the eye of a storm…You aren’t really there – you’re with the machine and that’s all you’re with.”

What struck me about this is twofold. First, I was caught off guard that the addiction has nothing to do with money, but the addiction of play itself. Second, I was surprised to see echoes of this in video game’s obsession with “the zone.” Indeed, the more the book went on, the more obvious it became that what Schüll’s subjects called “the machine zone,” the video game world calls “flow state.” They are the same thing.

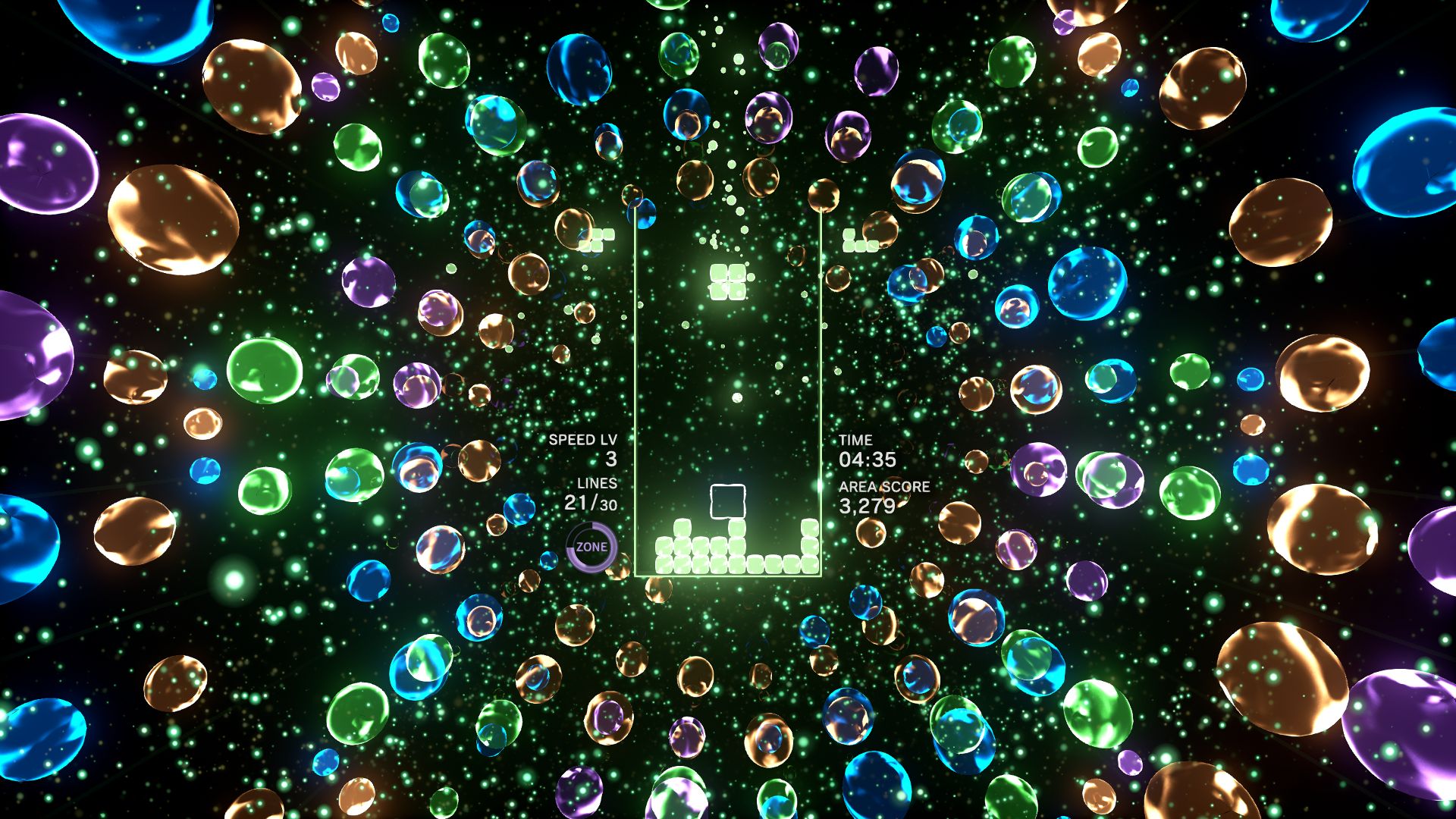

In games, we prize “the zone” in everything. It has become the ultimate goal for many contemporary designers, and is viewed as an unimpeachable good. This goes all the way back to the arcades, when the best works gave players a kind of trancelike condition, wide eyes drinking in the bombardment of audiovisual detonations. “The zone” lives on today in MMOs, in MOBAs, in our roguelikes and sports simulations. It’s almost harder to find a game that isn’t trying to induce flow state than to find one that is.

And there are decent reasons for that. In an NPR interview, psychologist Kate Sweeney speaks of the benefits of flow state:

Flow is really good for us. It gives us a lot of positive emotions, but it's also especially well-suited to times when we're really in our heads, when we're worried about the future, when we're ruminating about something and we just can't turn it off. Flow is a pretty good off switch for that kind of thinking.

Schüll, for her part, speaks of the expressive power of gambling machines, and she links the appeal of flow state specifically to its dependable consistency. In a time of increasing stress and precarity, flow state allows players to “manage their affective states and create a personal buffer zone against the uncertainties and worries of their world.” It is perhaps the purest form of escapism. With regards to video game’s penchant for flow state, Sweeney says: “There's really two groups of people who know a lot about flow. That's psychologists and video game designers. And video games are really kind of, as a whole, built for exactly this purpose.”

This is more or less the thinking of video game designers these days – flow state is good. It is its own kind of pleasure, a balm to the cacophony of contemporary existence. What’s less discussed or understood, however, are the problems with flow.

To reiterate, gamblers are not playing for money. Schüll notes: “Contradicting the popular understanding of gambling as an expression of their desire to get ‘something for nothing,’ [one gambler] claimed to be after nothingness itself.” Indeed, core to the flow state is a feeling of detachment, isolation, the destruction of space and time: one researcher says it “facilitates the dissociative process…[their clients] don’t talk about competition or excitement – they talk about climbing into the screen and getting lost.” This comports with my own experiences of playing “flow state” video games. There is an abandonment of time, a fuzziness, a loss of the self. In my League of Legends games, I can hardly remember playing; it felt more like a blurry wash of overlapping colors. My friends who play games have had similar experiences.

The first problem with this is loss of control. Schüll speaks of gamblers who play longer than they actually want to, and spend more than they want to. In fact, research shows that the majority who gamble regularly have had that experience. Flow state has its pleasures, certainly, but they are pleasures we should opt into. In gambling this gets weaponized in material and understood ways. The gambling world is filled with people who’ve undergone bankruptcy, lost their savings, and ended up in addiction clinics. Within video games, you have (so called) free-to-play games which chase the same thing: Game Marketing Genie has a page proudly evangelizing the techniques free-to-play developers can wield to catch “whales,” or players who “are massive spenders” (think thousands of dollars). You will not be surprised to learn that these techniques sound an awful lot like slot machines.

But what struck me in Schüll’s book is what lies beneath this monetary predation. Casinos’ slot machines have fine tuned their flow states to such a degree as to bring about a shockingly total veil from the surrounding world. She describes flow state as being the highest form of isolation – isolation from the world around you, from the flow of time, and from your very self. You aren’t there: all that’s left is the game in front of you.

The totality of this pull is best described in Schüll’s harrowing accounts of paramedics’ attempts to resuscitate heart attack victims on the casino floor. She recalls one such event:

By chance, the surveillance camera had been trained directly on the victim, who is playing at the tables. He rubs his temples, leans back, and tries to clear his head – then collapses suddenly onto the person next to him, who doesn’t react at all. The man slips to the floor in the throes of a seizure and two passersby stretch him out, one of them an off-duty ER nurse. Few gamblers in the immediate vicinity move from their seats.

The whole thing takes nine minutes, and, luckily, the man is saved, and walks away under his own power. But throughout all of this – nine minutes of saving a man’s life – Schüll realizes with horror: “Despite the unconscious man lying quite literally at their feet, touching the bottoms of their chairs, the other gamblers keep playing.” It’s like they aren’t even there; like they’ve dissolved into the game itself. Not even a dying man can shake them from their stupor. Schüll recalls, “It was not uncommon, in my interviews with casino slot floor managers, to hear of machine gamblers so absorbed in play that they were oblivious to rising flood waters at their feet or smoke and fire alarms that blared at deafening levels.”

Schüll labels the relationship between casino games and players as a kind of “collusion.” There are two halves of this relationship – the game, and the player – and the player just wants to play. They want escape and suspension – the “flow state” – and on the other side is the game, which wants to take money from you, or your time. And these relationships are not symmetrical. As we enter into these flow states, we lose control; and all the while we’re gone, the game furthers its own ends. It’s hard to feel very good about this sort of flow state, where you are effectively trapped in its gravity. It doesn’t feel like what Sweeney is talking about when she describes the positive benefits of an “off switch.”

It’s no secret that casino games are addicting. As Schüll (who, if it’s not clear by now, I am deeply indebted to for this piece) lays out, in 1980 the American Psychiatric Association endorsed “pathological gambling” as a specific diagnosis. This would be unambiguously good if it weren’t for the fact that their report “emphasized ‘gambler’s inability to resist internal impulses.’” This lays the groundwork for the creation of categories of gamblers – the “normal” gamblers, who have full control of their impulses, and thus can gamble safely; and the “problem” gamblers who cannot help but fall into addiction. This shifts the blame from the machines to the players. Games don’t addict people, some people just struggle to keep themselves in check.

So how many people do get addicted? If we take the gambling industry at their word, in the US 3-4% are either “problem” gamblers or addicts. But this number is against the entire US population. How many of us even have access to casinos? If instead we compare against only the number of people who are regular gamblers, then the number leaps as high as 20%. The numbers for video games are harder to parse. It seems most numbers hover around 4% of players have a video game addiction – here’s one article that cites the range as 1-10% – but these sites don’t make distinctions between addiction and what Schüll calls “problem” players. That is, there are people whose relationships to video games are fully destructive – this number is around 4%. But how many have relationships that are materially harmful, without rising to the level of “addiction?” One study from University of Michigan put the number between 14.6 - 18.3%, looking purely at Steam games, which is alarmingly close to casino games...

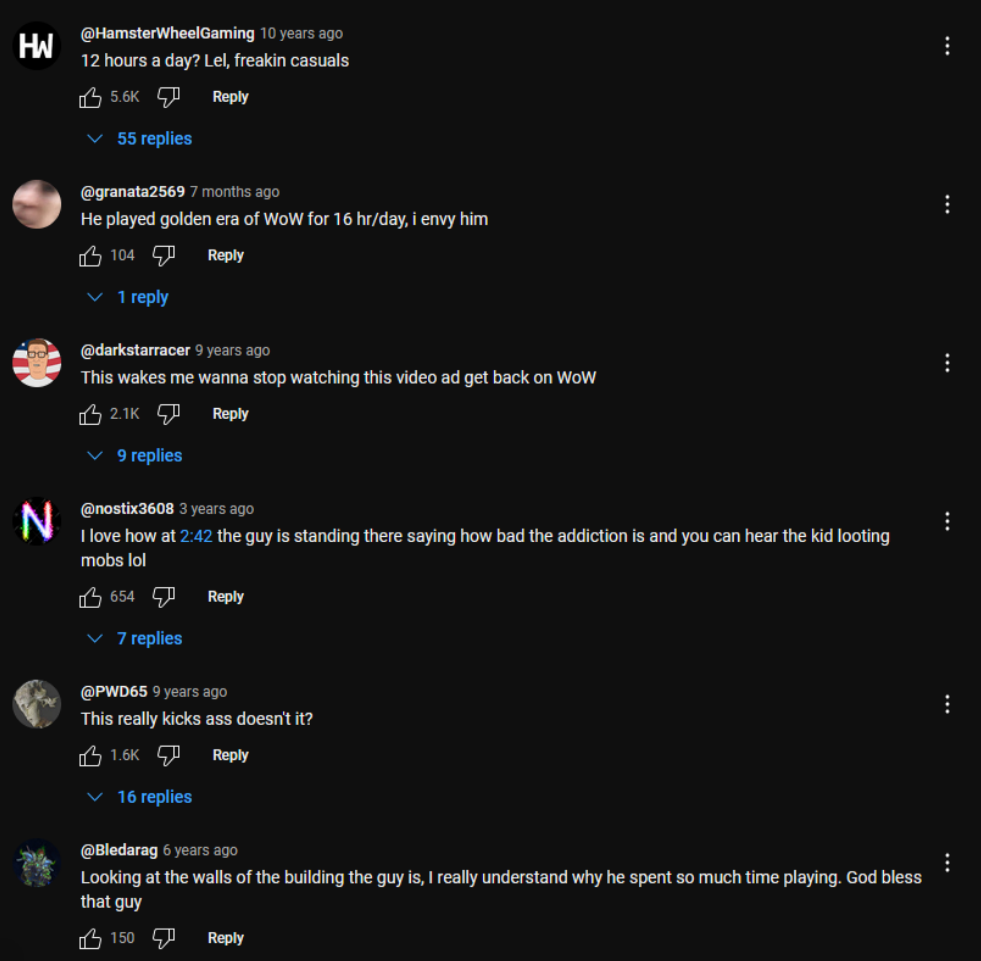

It wasn’t that long ago that video game’s uncomfortable relationship with addiction was out in the open. Here’s a news segment from 2006 on a teenage boy’s addiction to World of Warcraft.

It’s somewhat quaint in today’s light – over-the-top music, a reporter who doesn’t understand his subject (“you call the people you play with your friends?”). But then again, what they’re describing, playing for 12 hours straight with regularity, is unquestionably an addiction. The video’s comments are filled with people jokingly remembering the same experience:

Today, there is a bizarre doublethink in the games world when it comes to addiction. The most recent example is Balatro. In their review, ScreenRant declared: “Balatro is an addictively delicious, menacing creation which devours hours without mercy,” before giving it 5 stars out of 5. The game’s Steam comments are overrun with people saying more or less the same thing:

And this attitude is all over social media, discord – it’s the way everyone talks about this game, with a wink and a nod. It’s the way I myself talked about it. It may be addicting, but if it’s fun what’s the problem? Of course, this goes beyond Balatro. Before Balatro it was Stardew Valley, or Fortnite, or Slay the Spire...

All of this is deeply entangled with Schüll’s illuminations on gambling addiction: the player’s “aim is not to win, but to continue.” In the video game world, there is an obsession with playtime. No one will buy your game if it isn’t 30 hours, 50 hours, 100 hours. I used to think this was driven by a crude form of evaluation – more time per dollar equals a better bargain. But this has never made much sense, as no such pressures exist in film, literature, music, etc. It wasn’t until reading Schüll that it clicked for me – it has nothing to do with temporal-money exchange rates, but addiction. We are playing to keep playing – it almost doesn’t matter what you put there, just so long as we can continue.

And video games, it seems, have been happy to oblige. So enormous and all-consuming have these machines become that all anyone plays anymore are the most addicting examples. In Matthew Ball’s excellent “The State of Video Gaming in 2025,” he finds that of all time spent playing PC / console games, a shocking 91.5% went to only 8 games. Of the remaining 6.5%, half of the pie was claimed by 4 titles. The final 3.4% of playtime allocation is simply labeled: “everything else.” Certainly some of this is due to the colonisation of artforms by capital – every medium is reckoning with monopolization. Artists at the margins are finding less and less room for air. But video games’ monopolization is unique, and players’ hunger to throw themselves at the same works night after night for years has no parallel (beyond perhaps television, which has its own problems with addiction). For example, in 2019 the top 6 highest grossing films made up 39% of all domestic earnings in the US – an appallingly high number, but barely more than half of video game’s top 6 earners, which came to a whopping 75%. Certainly, we have an addiction problem. We’ve let a tiger into our home and decided to learn to live with it.

The uncomfortable truth is there is something inherently addicting about video software. Schüll details the rise of “machine gambling” (slot machines, video poker, etc) in the US, which began in the 80s. Until then, casinos were dominated by tabletop games like poker, craps, or black jack. By the end of the 90s and into the 2000s, the ratios had essentially flipped: physical poker tables were replaced by video poker machines; craps tables were replaced with slot machines. The reason for this, as Schüll notes, is that people who played “video gambling devices became addicted three to four times more rapidly than other gamblers…even if they had regularly engaged in other forms of gambling in the past without problems.” Studies that distinguish between digital and tabletop gambling “consistently find that machine gambling is associated with the greater harm to gamblers.” In 2000, one addiction clinic in Las Vegas admitted that over 90% of their patients were addicted to video gambling.

The first reason for this lies in the software. Video games allow for a higher “event frequency,” meaning they allow for instantaneous changes and rapid restarts. You can play again almost before you’ve even consciously decided to. The other reason is that video gambling games are solitary experiences, which allow for an “uninterrupted process…a steady, trancelike state.” This steadiness is crucial to “the zone.”

So, let’s take chess. I’ve had games where I’m doing well, controlling the board, only for things to fall away from me in a last minute defeat. It can feel unsatisfying, so I ask to play again. Perhaps this has happened to you. But by the time it takes us to agree to a rematch, reset the board, settle in for another round…I’ve realized I don’t actually want to play again. I just thought I did, out of a momentary impulse. The danger with video games is they let us dive headlong into another round before coming up for air, letting our head resort itself to find we don’t want a second round after all. At an NYU talk, Schüll is asked what it is about video games that creates this loss of control in players. “I think it has to do with the fact that the immediacy of response,” she muses, “and the kind of data crunching that this machine is doing, surpasses the time and space of the body to compute…there’s this sense that your own intention is already appearing. It’s so fast and so immediate that something in the system is tricked…and I think that is [a result of] the digital.” And it’s hard to find fault with that idea. Machine gambling has been called “‘the most virulent strain of gambling in the history of man,’ ‘electronic morphine,’ and, most famously, ‘the crack cocaine of gambling.’”

Even in hobbyist games, I have encountered this compulsion. I recently played Daniel Benmergui’s Dragonsweeper, from which I sense no malice at all. But I found myself addicted. I would play for 30 minutes, an hour more than I wanted to. Before I could rip myself out, my body had already hit the restart button, the game had already reformed, and I was already considering my first move. I was hooked. One gambler tells Schüll that to reach the “machine zone” is to maintain an “ever-present awareness of being in a destructive process…Even as part of one’s mind is hopelessly lost to it, lurking in the background is a part that is sharp and aware of what is going on but seems unable to do much to help.” Yes. That is precisely the feeling. I have felt it in pancelor’s Make Ten, and in my good friend Hao’s Bokuto Simulator. I name these games specifically because I am certain they hold no ill intentions. They are free games, made for fun, by designers I trust and like. And even here I have encountered compulsion, a dangerous dance with addiction.

It seems clear to me that the danger of the form has never been taken very seriously. It doesn’t matter that people have been decrying video game’s addictive qualities for decades (we are tickled by the hold that Candy Crush has on players, rather than alarmed by it), as those people are just stick-in-the-muds. They’re against fun. But in our failure to look seriously at these forces, we have thoughtlessly reproduced them at every level of the medium. This is not to say that every game boils down to addiction, but that this force can be encountered anywhere – live service games, open worlds, flight sims and hobbyist works. And we see these addictions and praise it for “good game design.” We can’t stop playing – isn’t that great?

It is not an accident, though, that these elements have found their way onto our computers. I don’t know exactly when this began, but sometime in the 2000s or 2010s, AAA studios began to bring psychologists into their design rooms. Together, they would probe the human mind for vulnerabilities they could exploit in the pursuit of player retention. In 2017, an Epic Games developer gave a talk “[dispelling] the neuromyths around dopamine,” titled “Throwing Out the Dopamine Shots: Reward Psychology Without the Neurotrash.” It is an appallingly uncritical look at the psychological pain points designers can weaponize against players. One slide, subtly titled “Feedback, Feedback, FEEDBACK!!! [emphasis their own]” reminds us: “If players don’t know they got a reward, they can’t try to get it again. If players don’t know why they got a reward, they can’t do the behavior again.” It is brazenly uninterested in aesthetics, art, or even entertainment: the ultimate goal ends with the player still playing. Repeat, repeat, repeat. Later on, he talks about the beauty of operant conditioning, and “variable ratios” (think loot boxes, percent-chance rewards, and so forth). He mentions the latter is “used in gambling,” before encouraging everyone in the room to use it themselves. It is no wonder, indeed, that Epic Games has created perhaps the most addicting PC game on the planet.

Beyond the shamelessly predatory exploitation of players’ brains against the body, games’ relations to addiction lurk in other corners, too, in less overt forms. Sid Meier lays out his idea of “one more turn” (which he says applies “to almost every game”) in a 2010 GDC talk. “One more turn,” he says, is a state where “the player is constantly leaning forward; they’re anticipating things that are going to happen later…[and] wondering what’s around the next corner.” Meier says that “it all comes back to this idea of replayability.” Luke Plunkett describes the phenomenon aptly in a recent review of Civilization VII. Throughout the piece, he plasters the game with criticism, only to admit: “Despite everything I’m about to say [that is, the negative review to come], I have played this game almost non-stop for the past week, even when I haven’t had to.” Where “one more turn” may have appeared by mistake in something like Bokuto Simulator, it has been deliberately designed into the fabric of Civilization VII or Fortnite.

Outside of turn-based games, we can find the “one more turn” phenomenon in modern open world games. In a NoClip documentary, a CD Projekt Red developer recalls The Witcher 3’s “rule of thirty seconds”: “We did some tests, and we found that the player is focused on stuff which we produce…every thirty seconds they should see something, and focus on it, like a pack of deer, some opponents, some NPCs wandering about.” It is eerily similar to Schüll’s accounts of casinos, whose mazelike interiors are deliberately designed to confront players with machines at constant intervals, always in front of them. Here we can recall Schüll’s account of flow state’s dependency on an “uninterrupted process” – if open world games don’t dangle new centers of attention in steady intervals, the process can be disrupted, and the play might end. “Although a casino’s maze layout should not overclarify what lies ahead,” Schüll explains, “it should clarify its pathways enough to prevent stalling and keep movement flowing towards machines.” Bill Friedman, the godfather of modern casino design, says it more simply: “Strong guidance is needed from design cues.”

This has become the focus of contemporary level design principles, linear and open world games alike. The player should barely have to think about navigation. In 2013, Dan Taylor, a level designer at Square Enix, presented a GDC talk titled, “Ten Principles for Good Level Design.” The first principle is stressed: “For a smooth and enjoyable experience [note the term ‘smooth,’ the uninterrupted flow], the player should always know exactly where to go.” Taylor goes on to explain that the player should never be confused, and takes this into the third principle: “The player needs to be in no doubt as to what he or she has to do in your level. And you should provide them with clear objectives, so waypoints, other navigational aids, etc.” Later on he cites Raph Koster’s A Theory of Fun, which points to the human mind’s predilection for patterns. If the pattern is completed or ends, then the enjoyment ends with it. Taylor muses, “How do we prolong this enjoyment through level design?” How do we keep the players playing? Do we have to let them go?

Indeed, level design scholarship has always troubled me in its obsession with player control – it’s almost impossible to find writings on the aesthetics of level design. I teach a class on digital game environments, and I am constantly fighting against the current of contemporary level design ideology. No matter how much I try to get my students to reflect on how a space makes them feel, they invariably focus on what it’s making them do. I speak with them of lighting, of the difference between soft light and hard light, warm and cold, the emotional conveyance of shadows and form – but inevitably they focus on how lights lead the player to the next path instead. When I try to get them to think of the disruption of sightlines, how the act of piecing together a picture makes them feel and react, they instead focus on where the sightlines are leading their eye…once more, to the next path. Tell me where to go. Level design has become a tool of domination and control. Never let the player get lost, lest they think about stopping.

I want to put all of this another way. There is a card game called Nertz (or Double Solitaire, as my family calls it), which I play with friends. Here’s how it goes. We gather around a table – a big table – and we all have our own deck of cards. First, we have to shuffle – we all have our own rituals here; I like to shuffle seven times, others more or less – and we arrange our cards in careful columns. When the game starts, we’ll be playing our own game of solitaire, and in the large expanse of open table in the center, we’ll be playing a shared game of competition. It’s a realtime game, so one must play their cards before another beats them to it, which leaves us lunging our bodies hopelessly to drive a two of hearts down while we still can. I love this game. When we play, we are soundboards for yelps and yawps, triumphs and tragedies. We play in rounds, and when a round concludes we pause and count our cards, and here again we roar and we weep. Then we gather our cards, shuffle, and wait for our friends to do the same. It’s a beautiful ritual.

When the pandemic hit, Zachtronics built an online version of this game, and this, too, I play with friends. But it isn’t the same. What began as a social game transforms into digital isolation. There is a hypnotic effect to the flashing screen, and, most troubling, it becomes difficult to put down. We play again, and again, and again, past the point where any of us still want to. It becomes a game of addiction. In all of these cases, I think there are interesting games in the dirt. Beneath the layers of addiction and compulsion, the flashing lights and auto restarts, we can find games that enrich us, that add to our lives. But I don’t know how to reach these places when I lose myself in the process. We are gaining player retention, but losing play – what we’re left with are addiction machines. Schüll recalls speaking with someone high up in the gambling world, who was remarkably candid. He says, “Some other countries have a healthier attitude towards gambling. They don’t treat it like a straightforward consumer transaction – they treat it for what it is, something in our human nature that can always go out of control. And as a result it’s not as self destructive because there are limits placed on the activity. With those limits in place the activity is tolerated as a natural form of human behavior and it doesn’t get out of hand the way it does here in the states, because there is a net. It has less dark energy there. Here, we let people destroy themselves.”

So, what to do about all of this? This is what I keep asking myself. I think the first thing to note is that games haven’t always been this way. Lately I’ve been playing a lot of games from the 90s and 2000s, and it is astonishing how different they feel. Take the world designs of Ocarina of Time and Assassin’s Creed Odyssey: both unquestionably commercial works, but the former is rather empty and austere, and the latter follows The Witcher 3’s rule of thirty seconds. In the former you wonder openly about where to go next, and in the latter you are never left to your own thoughts. But these older games are wonderful. Not all of them, of course, but there is nothing lost in being present with a game rather than losing yourself to it. In fact, it is more enriching.

And I think there is a tremendous responsibility in crafting these games. Especially so with so-called “endless” games. There are pleasures in flow state, but it risks isolation, forgetfulness, and un-being. It requires a great deal of care. I’ve been thinking a lot about the idea of “coming up for air” – is this game driving me deeper and deeper, or is it pushing me back to the surface? Am I choosing to play? One thought is to put in cooldown timers on instant restart games. You get three restarts, then a five minute time out period. If you still want to play, come back then. It might be naive, but maybe it would work. I’m not sure.

Regardless, it is far better to design knowing all this than to pretend it isn’t there. In an early passage, Schüll speaks with Connie Willis, the director of IGT’s Responsible Gaming division, who says that their designers “don’t even think about addiction – they think about beating Bally and other competitors.” Which Schüll asserts to be part of the problem. We’re not thinking about addiction. How can we not think about addiction? When it is a spector hovering over everything we do? When it's a field we must pass through as players and designers?

In Tracy Fullerton’s Game Design Workshop, she talks with joy and optimism about how games have become a dominant part of our culture. She cites a poll by the Entertainment Software Association which reveals that 61% of us are playing games for at least an hour every week. 68% percent play to “pass the time or relax,” and 30% play for “immersion / escape.” But it’s hard for me to share in Fullerton’s excitement. It's hard for me not to feel disheartened by modern video games. We aren’t playing curiously, seeking out meaningful works – we are seeking out time killers, anesthesia, endless content. We are playing the same handful of games over and over, we are screaming at the computer, we are getting harassed by teenagers and nazis. We are having every step of our lives “gamified.” We are seeing sports betting legalized; child labor farms monetized and marketed as get-rich-quick schemes in Roblox; and military propaganda pipelines in video games for children (not to mention the games made for actual soldiers, for actual warfare). So, it’s true: 61% of us are playing games for at least an hour every week. And how should we measure the cost?

Instead, I think about the game of Nertz, beneath the compulsion loops. I can’t help myself. I wonder how much richer the video game landscape might be if we could shed these tools of addiction altogether. If we could play the games locked up inside them – if we could stop when we’re ready, and rise back into the world feeling whole.